Breast Augmentation Complications

Consultations offered at our four convenient locations in La Jolla, San Diego, Newport Beach and Beverly Hills

Breast Augmentation complications are rare, and hundreds of thousands of women enjoy the beautiful results of their breast augmentations safely every year. However, for those who are considering a breast augmentation, or who are worried that something isn’t quite right with their current implants, it’s important to know the risks that accompany this popular procedure. At La Jolla Plastic Surgery & Dermatology, Dr. Richard Chaffoo and his staff ensure that each of their patients has the information they need to make a confident decision about their aesthetics. If you’re interested in learning more about this procedure and want to speak with an expert, contact our offices across Southern California to make an appointment for a personal complimentary consultation. Call (800) 373-4773 for our offices in La Jolla, or (619) 633-3100 for our San Diego location. Those in the Los Angeles or Orange County areas can call (310) 774-2496 to speak with a staff member in Beverly Hills, and our Newport Beach offices can be reached at (949) 996-9964.

Contents

- 1 Capsular Contracture

- 2 Hematoma

- 3 Altered Nipple Sensation

- 4 Rippling

- 5 Implant Rupture/Failure

- 6 “Bottoming Out” Of Implant

- 7 Seroma

- 8 Asymmetry

- 9 Infection

- 10 Scarring

- 11 Delayed Healing Of Surgical Incisions

- 12 Pneumothorax

- 13 Anesthesia

- 14 Synmastia

- 15 Numbness to Inner Arm

- 16 Lateralization Of Breast Implant

- 17 Loss Of Breast Feeding

- 18 Implant Exposure

- 19 BIA-ALCL

- 20 Inadequate Cosmetic Result/Reoperation

- 21 Deep Venous Thrombosis (DVT)/Pulmonary Embolus

- 22 References

Capsular Contracture

This is the most common complication following breast augmentation surgery and the main reason reoperation is necessary. Reoperation varies from 15% – 30% in numerous studies with approximately 50,000 people undergoing such surgery each year. (1-9) The cause of capsular contracture is most likely multifactorial or the result of not one but several factors some of which may not be known at this time. Several factors which have been discovered that result in capsular contracture include the use of smooth-surfaced breast implants, placing the implants above the muscle (subglandular), a biofilm reaction to the surface of the implant, and infection. (10)

Capsular contracture is a local complication that is due to an excessive fibrotic foreign body reaction of the body to the presence of a breast implant. This results in a hardening and firmness to the breast implant, distortion in the shape of the breast, and pain in more severe cases.(11) The degree of capsular contracture was described by Baker and divided into 4 categories. Baker’s 1 feels and looks like a normal breast. In Baker’s 2, the breast feels firm but does not appear distorted. In Baker’s 3, the breast feels firm and looks distorted in shape. In Baker’s 4, the breast is also painful.

Two oral medications have been proposed to reduce the severity of capsular contracture and reduce its initial occurrence. These are “off-label” treatments and no well-designed studies have proven their benefit in either situation. These two medications are known as Accolate and Singular (14), both used in the treatment of asthma.

The surgical treatment of capsular contracture is usually reserved for Baker’s 3 and 4 cases. Long-term elimination of recurrent capsular contracture is most likely when the breast implant capsule is surgically removed, called a capsulectomy, along with the removal of the existing breast implant and replacement with a new implant. Capsulectomy is considered the “gold standard” by many plastic surgeons.(15) Some studies suggest that combining capsulectomy with placement of a material called acellular dermal matrix or ADM (16) may further reduce the recurrence of capsular contracture but well-designed scientific studies are lacking.

Hematoma

This is one of the most common complications following breast augmentation surgery, occurring in 1% of women undergoing breast surgery in a study involving over 70,000 aesthetic surgery patients from Vanderbilt University over a 5-year period.(17) This study discovered that risk factors for bleeding after breast augmentation surgery and hematoma formation included advancing age, higher BMI, diabetes, and combination procedures (breast augmentation and another procedure).

Altered Nipple Sensation

While many women who undergo breast augmentation surgery notice altered nipple sensation after surgery, only a small percentage of them notice a permanent alteration or reduction in sensation following this surgical procedure. While all studies to address this issue involve relatively small sample sizes, the majority of women noticed a return to normal nipple sensation within 6 months after breast augmentation surgery.(18) A recent study also suggested that final nipple sensation after breast augmentation surgery is no different whether the procedure is performed within the breast crease (inframammary approach) or around the nipple (periareolar approach).(19)

Rippling

Visible or palpable folds in a breast implant can occur in several situations resulting in rippling. Rippling can occur in patients who are very thin with little breast tissue coverage of the implant, placement of the implant above the pectoralis muscle (subglandular location), placement of large implants for the patient’s frame, and the use of saline implants. Correction can be difficult and incomplete but needs to be based upon the causative factor(s). Selected cases may benefit from site change from subglandular to subpectoral (beneath the pectoralis muscle), exchange from saline to silicone implants, the addition of fat transfer to the breasts,(20) or the use of acellular dermal matrix (ADM) to cover the implant.(21)

Implant Rupture/Failure

Failure or rupture of modern-day breast implants is an uncommon occurrence following breast augmentation surgery and is most commonly caused by instrumental damage to the implant during surgery.(22) Historically, silicone implants have failed and ultimately leaked at a rate of 1-2% per year, and MRI scan remains the gold standard to evaluate the integrity of a breast implant, especially in cases of a silent rupture (rupture only noticed on radiological studies).(23)

“Bottoming Out” Of Implant

Bottoming out and double bubble represent the second most common reason for revision surgery following breast augmentation surgery. This occurs when the inframammary fold (breast crease) ligaments that represent the lower limits of the breast support are disrupted during surgery. When this happens, the breast implant is not supported and can easily “bottom out” and drop below the lower border of the breast. A “double bubble” can be created by the implant with a portion of the implant lying below the breast crease and the upper portion of the implant lying above it.(24) Several surgical options may be used by the surgeon to correct this deformity including capsulorrhaphy (tightening the breast implant capsule) and the use of acellular dermal matrix (ADM).(25)

Seroma

Along with hematoma, seroma represents one of the most common early complications following breast augmentation surgery. It typically occurs within the first month of surgery as a collection of fluid around the breast implant and has an incidence of 0.1 – 2%.(26),(27) Risk factors associated with seroma formation include high BMI, large implant size, implant placement beneath the gland (subglandular), and smoking.(28) Treatment may include the placement of a catheter by a radiologist or the plastic surgeon to drain the fluid for several days. Further surgery may involve the removal of the capsule and breast implant.

Asymmetry

Breast asymmetry following breast augmentation surgery is relatively common since preoperative asymmetries are quite common even before surgery in most patients. A recent study confirmed that asymmetries occur in relation to breast mound position, inframammary fold position, nipple/areolar size and position, and underlying chest wall deformities. The authors studied 100 patients who were undergoing breast augmentation surgery and discovered that 88% of them had at least one of the above asymmetries preoperatively and nearly three-quarters of them demonstrated more than one type of asymmetry.(29) Even when plastic surgeons choose different sizes, styles, or shapes of implants for each breast, postoperative asymmetries remain in many cases since breast augmentation surgery only affects the shape and volume of the breasts but does not correct any of the other asymmetries present preoperatively. Some authors had advocated the use of sophisticated software programs that can more accurately evaluate the patient’s asymmetries and suggest implant choices preoperatively. While these programs provide improved patient education and communication with their plastic surgeons, postoperative asymmetries are still quite common.(30)

Infection

Infection of a breast implant following breast augmentation surgery is uncommon but ranges from 1.1 – 2% in several studies.(31),(32) The most common bacteria responsible for breast implant–associated infections include Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia, Pseudomonas, Propionibacterium, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Corynebacterium.(33) Treatment usually includes intravenous antibiotics, cultures, and often the removal of the breast implant. Once the infection resolves, the plastic surgeon can usually replace the implant in an outpatient setting.

Scarring

It is well known that the patients’ perception of scars play an important role in the outcome and patient satisfaction following an elective cosmetic surgical procedure.(34) A surgical scar is created despite where it is made for placement of the breast implant: around the nipple, inframammary fold (breast crease), or the armpit (transaxillary). The appearance of the scar depends upon its age, patient skin type, healing or infection of the scar, patient age, and exposure to sunlight. The scars may be red, raised, painful, or itch long after they have formed.(35) However, most patients seem satisfied with the appearance of the scars following breast augmentation regardless of which incision the surgeon chooses.(36) While scars improve with time, silicone sheeting, injection of the scars with dilute Kenalog, and lasers are used at times to lessen their appearance.

Delayed Healing Of Surgical Incisions

This is a relatively rare occurrence following breast augmentation surgery but more common in patients who continue to smoke before and following surgery. Smoking is known to contain several chemicals that directly impair wound healing including nicotine, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen cyanide. Smokers tend to have a higher incidence of complications following breast surgery as compared to non-smokers. (37)

Pneumothorax

This is a relatively rare complication following breast augmentation surgery.(38) The incidence of pneumothorax is unknown but was reported to occur in 0.42% of plastic surgeons who were members of the California Society of Plastic Surgeons and responded to a survey.(39) 43% of cases were thought to be due to direct injury to the underlying lung tissue at the time of surgery, 16% from a rupture of existing abnormal lung blebs, 37% due to needle injection of local anesthesia, and 3% due to the anesthesia technique. About ½ of the cases were discovered during surgery and the rest in the postoperative time period. 55% were hospitalized and the remainder were treated as outpatients. Treatment varied dependent upon the severity of the lung collapse (pneumothorax) and included observation to insertion of a chest tube to re-expand the air. Symptoms can include chest pain or tightness, shortness of breath, or no specific symptoms in cases of a small pneumothorax. It is diagnosed by physical exam demonstrating decreased breath sounds and confirmed by chest x-ray.

Anesthesia

Complications of breast augmentation surgery related to anesthesia are rare and include reaction to the anesthetic agent(s), local anesthesia toxicity, pneumothorax from injury to the lung pleura from an anesthetic needle injection, cardiovascular compromise, and respiratory arrest or respiratory depression. Preventable death from anesthesia is a very rare occurrence of less than 1 case in 100,000 patients (40) (41) with today’s drugs and anesthesia machines. Most of these complications are preventable and manageable when anesthesia is provided by board-certified anesthesiologists in an accredited and licensed surgery center or hospital setting.

Synmastia

This is a very rare but serious deformity which only seems to occur in patients who have undergone subpectoral breast augmentation (placement of the implants beneath the pectoralis muscle).(42)(43)(44) In these cases, there is a direct communication between both breast implants across the midline, reducing or eliminating natural cleavage. This is usually the result of the over-aggressive release of the pectoralis muscle medially and the fascia over the sternum.

Treatment can be difficult and a variety of approaches have been suggested including reattachment of the pectoralis muscle, closure of the breast implant capsules medially (capsulorrhaphy), and the use of acellular dermal matrix to eliminate the connection between both implant capsules.(45,46,47)

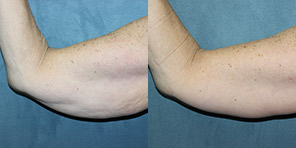

Numbness to Inner Arm

This is a rare complication and seems to occur when breast augmentation is performed through the armpit (transaxillary approach). A nerve that supplies sensation to the inner arm lies in the armpit and can be injured during surgery. It is possible to notice decreased sensation in the inner aspect of the arm. One study reviewed the experience of 500 surgeons who performed transaxillary breast augmentation and were members of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. The surgeons indicated that this complication occurred in about two-thirds of their patients but most resolved within a few weeks to several months with very few cases resulting in permanent numbness.(48)

Lateralization Of Breast Implant

This complication can occur in several situations. If the dissection pocket created for the breast implant is too large laterally then the implant can fall off to the side because the pocket is much larger than the diameter of the implant. When a breast implant is chosen that is much larger than the chest wall it is designed to lie above then the implant will extend into the armpit, the so-called “side boob”. These deformities can be corrected by tightening the implant capsule with permanent sutures to close off the lateral implant pocket called a lateral capsulorrhaphy. If the implants are too large in diameter then they can be removed and replaced with smaller implants that match the chest wall width and a lateral capsulorraphy can also be performed.

Loss Of Breast Feeding

Breast augmentation is most commonly performed on women during their reproductive years when lactation and breastfeeding are important. A large retrospective study was undertaken by three French universities to evaluate the impact on breastfeeding of breast augmentation surgery. The findings revealed that 75% of women in their study were able to successfully breastfeed after surgery. The type of implant, volume of the implant, and surgical incision had no influence upon breastfeeding in this group. 82% of patients who had their implants placed subpectoral (beneath the muscle) were able to breastfeed. However, only 17% of patients whose implants were placed subglandularly (above the muscle) were able to successfully breastfeed after breast augmentation surgery.(49) Another study concluded that the lack of breastfeeding following breast augmentation may be due to the small breast volume and enlarged areola in many women preoperatively which predisposes them to insufficient milk volume.(50)

Implant Exposure

This most commonly occurs when the implant becomes exposed to the outside through an inframammary incision. If there is no surrounding infection then it is sometimes possible for the plastic surgeon to save the implant and ultimately close the wound especially if the opening is small. Once the wound is large and there is significant infection then most surgeons will recommend intravenous antibiotics, removal of the breast implant, and replacement of the implant once the infection resolves.(51)

BIA-ALCL

Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA_ALCL) is a rare malignancy that is classified as a T cell lymphoma occurring in a delayed fluid collection around a textured breast implant or the surrounding breast implant capsule.(52)(53) Patients typically present with a spontaneous fluid collection around a breast implant or a mass in the breast implant capsule 2 – 10 years following breast implant placement for either cosmetic or reconstructive purposes. Diagnosis may be made by examining the fluid around the implant or the breast mass associated with the implant capsule. Further medical and surgical therapy is indicated based upon the extent of disease.

Inadequate Cosmetic Result/Reoperation

Recent FDA studies from two of the major US breast implant companies, Allergan and Mentor, indicate that breast augmentation surgery has up to a 20% reoperation rate following the first surgery and an even higher rate for the second surgery.(54) There are multiple causes of reoperation (55) following initial breast augmentation that include the following:

- Poor implant selection

- Oversized breast implants causing soft tissue stretch, capsular contracture, glandular atrophy

- Wrong implant shape selection resulting in patient dissatisfaction

- Improper surgical technique

Deep Venous Thrombosis (DVT)/Pulmonary Embolus

When a blood clot forms in a deep vein in the leg, it can dislodge and travel to the lungs causing a pulmonary embolus. This complication is extremely uncommon after breast augmentation surgery: reported to be less than 0.01% in a large study of over 45,000 cases. In fact, pulmonary embolus was not significantly more common when breast augmentation was combined with abdominoplasty (tummy tuck) occurring in only 0.06 – 0.1% of over 20,000 patients.(56)

References

- Spear SL, Murphy DK, Slicton A, Walker PS. Inamed Silicone Breast Implant Core Study Results at 6 Years. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2007;120(Supplement 1):8S16S. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000286580.93214.df

- Cunningham B. The Mentor Core Study on Silicone MemoryGel Breast Implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007 Dec;120(7 Suppl 1):19S-29S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000286574.88752.04. PMID: 18090810.

- Wong CH, Samuel M, Tan BK, Song C. Capsular contracture in subglandular breast augmentation with textured versus smooth breast implants: a systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(5):1224-1236. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000237013.50283.d2

- Handel N, Jensen JA, Black Q, Waisman JR, Silverstein MJ. The fate of breast implants: a critical analysis of complications and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(7):1521-1533. doi:10.1097/00006534-199512000-00003

- Pollock H. Breast capsular contracture: a retrospective study of textured versus smooth silicone implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91(3):404-407.

- Henriksen TF, Hölmich LR, Fryzek JP, et al. Incidence and severity of short-term complications after breast augmentation: results from a nationwide breast implant registry. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51(6):531-539. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000096446.44082.60

- Gylbert L, Asplund O, Jurell G. Capsular contracture after breast reconstruction with silicone-gel and saline-filled implants: a 6-year follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85(3):373-377. doi:10.1097/00006534-199003000-00006

- Burkhardt BR, Dempsey PD, Schnur PL, Tofield JJ. Capsular contracture: a prospective study of the effect of local antibacterial agents. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77(6):919-932.

- Adams WP Jr, Conner WC, Barton FE Jr, Rohrich RJ. Optimizing breast pocket irrigation: an in vitro study and clinical implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(1):334-343. doi:10.1097/00006534-200001000-00051

- Headon H, Kasem A, Mokbel K. Capsular Contracture after Breast Augmentation: An Update for Clinical Practice. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42(5):532-543. doi:10.5999/aps.2015.42.5.532

- Wolfram D, Rainer C, Niederegger H, Piza H, Wick G. Cellular and molecular composition of fibrous capsules formed around silicone breast implants with special focus on local immune reactions [published correction appears in J Autoimmun. 2005 Jun;24(4):361. Dolores, Wolfram [corrected to Wolfram, Dolores]; Christian, Rainer [corrected to Rainer, Christian]; Harald, Niederegger [corrected to Niederegger, Harald]; Hildegunde, Piza [corrected to Piza, Hildegunde]; Georg, Wick [corrected to Wick, Georg]]. J Autoimmun. 2004;23(1):81-91. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2004.03.005

- Spear SL, Baker Jr JL. Classification of capsular contracture after prosthetic breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 1995; 96: 1119-1123

- Scuderi N, Mazzocchi M, Fioramonti P, Bistoni G. The effects of zafirlukast on capsular contracture: preliminary report. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2006;30(5):513-520. doi:10.1007/s00266-006-0038-3

- Catherine K. Huang, MD, Neal Handel, MD, Effects of Singulair (Montelukast) Treatment for Capsular Contracture, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 30, Issue 3, May/June 2010, Pages 404–408, https://doi.org/10.1177/1090820X10374724

- Pereira Leite L, Correia Sa I, Marques M. Etiopathogenesis and treatment of breast capsular contracture. Acta Med Port 2013; 26: 737-745

- Cheng A, Lakhiani C, Saint-Cyr M. Treatment of capsular contracture using complete implant coverage by acellular dermal matrix: a novel technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(3):519-529. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829acc1e

- Varun Gupta, MD, MPH, Max Yeslev, MD, PhD, Julian Winocour, MD, Ravinder Bamba, MD, Charles Rodriguez-Feo, MD, James C. Grotting, MD, FACS, K. Kye Higdon, MD, FACS, Aesthetic Breast Surgery and Concomitant Procedures: Incidence and Risk Factors for Major Complications in 73,608 Cases, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 37, Issue 5, 1 May 2017, Pages 515–527, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjw238

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: February 2004 – Volume 113 – Issue 2 – p 701-707

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: May 2006 – Volume 117 – Issue 6 – p 1694-1698

- Munhoz, Alexandre Mendonça M.D., Ph.D.; Maximiliano, João M.D., M.Sc.; Neto, Ary de Azevedo Marques M.D.; Duarte, Daniele Walter M.D., M.Sc.; de Oliveira, Antonio Carlos Pinto M.D., M.Sc.; Portinho, Ciro Paz M.D., Ph.D.; Zanin, Eduardo M.D.; Collares, Marcos Vinicius Martins M.D., Ph.D.. Zones for Fat Grafting in Hybrid Breast Augmentation: Standardization for Planning of Fat Grafting Based on Breast Cleavage Units. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: October 2022 – Volume 150 – Issue 4 – p 782-795 doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000009605

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 130(5S-2):70S-85S, November 2012.

- Handel N, Garcia ME, Wixtrom R. Breast implant rupture: causes, incidence, clinical impact, and management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(5):1128-1137. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a4c243

- Hölmich LR, Fryzek JP, Kjøller K, et al. The diagnosis of silicone breast-implant rupture: clinical findings compared with findings at magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;54(6):583-589. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000164470.76432.4f

- Salgarello, M., Visconti, G. Staying Out of Double-Bubble and Bottoming-Out Deformities in Dual-Plane Breast Augmentation: Anatomical and Clinical Study. Aesth Plast Surg 41, 999–1006 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-017-0918-8

- Handel, Neal M.D.. The Double-Bubble Deformity: Cause, Prevention, and Treatment. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: December 2013 – Volume 132 – Issue 6 – p 1434-1443 doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000434405.91316.96

- Lista F, Tutino R, Khan A, Ahmad J. Subglandular breast augmentation with textured, anatomic, cohesive silicone implants: a review of 440 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(2):295-303. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182958a6d

- Ballard TNS, Hill S, Nghiem BT, et al. Current trends in breast augmentation: Analysis of 2011-2015 maintenance of certification (MOC) tracer data. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39:615–623.

- Sforza M, Husein R, Atkinson C, Zaccheddu R. Unraveling factors influencing early seroma formation in breast augmentation surgery. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37:301–307.

- Rohrich, Rod J. M.D.; Hartley, Winfield M.D.; Brown, Spencer Ph.D.. Incidence of Breast and Chest Wall Asymmetry in Breast Augmentation: A Retrospective Analysis of 100 Patients. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: December 2006 – Volume 118 – Issue 7S – p 7S-13S doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000049636.17522.1B

- Liu, Chunjun M.D., Ph.D.; Luan, Jie M.D., Ph.D.; Mu, Lanhua M.D., Ph.D.; Ji, Kai M.D.. The Role of Three-Dimensional Scanning Technique in Evaluation of Breast Asymmetry in Breast Augmentation: A 100-Case Study. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: December 2010 – Volume 126 – Issue 6 – p 2125-2132 doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f46ec6

- Araco A, Gravante G, Araco F, Delogu D, Cervelli V, Walgenbach K. Infections of breast implants in aesthetic breast augmentations: A single-center review of 3,002 patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007;31:325–329.

- Cohen JB, Carroll C, Tenenbaum MM, Myckatyn TM. Breast implant-associated infections: The role of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the local microbiome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136:921–929.

- Cohen JB, Carroll C, Tenenbaum MM, Myckatyn TM. Breast Implant-Associated Infections: The Role of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the Local Microbiome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5):921-929. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000001682

- Randquist C, Por YC, Yeow V, et al. Breast augmentation surgery using an inframammary fold incision in Southeast Asian women: patient-reported outcomes. Arch Plast Surg. 2018;45:367–374.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. Scars. Available at https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/scars. Accessed May 25, 2021.

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery – Global Open: May 2022 – Volume 10 – Issue 5 – p e4313.

- Lesmes GR. The American Journal of Medicine | The Effects of Cigarette Smoking: A Global Perspective | ScienceDirect.com by Elsevier. www.sciencedirect.com. Published June 19, 1991. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/the-american-journal-of-medicine/vol/93/issue/1/suppl/S1

- Codner MA, Cohen AT, Hester TR. Complications in breast augmentation: prevention and correction. Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28(3):587-596.

- Pneumothorax as a Complication of Breast Augmentation. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: September 15, 2005 – Volume 116 – Issue 4 – p 1122-1126.

- Lienhart A, Auroy Y, Pequignot F, Benhamou D, Warszawski J, Bovet M, Jougla E: Survey of anesthesia-related mortality in France. Anesthesiology 2006; 105:1087–97

- Li G, Warner M, Lang BH, Huang L, Sun LS: Epidemiology of anesthesia-related mortality in the United States, 1999–2005. Anesthesiology 2009; 110:759–65

- Spear, S.L., Synmastia after Breast Augmentation. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: December 2006 – Volume 118 – Issue 7S – p 168S-171S.

- Spence, R. J., Feldman, J. J., and Ryan, J. J. Synmastia: The problem of medial confluence of the breasts. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 73: 261, 1984.

- Fredricks S. Medial confluence of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75(2):283-284. doi:10.1097/00006534-198502000-00040

- Chasan PE. Breast capsulorrhaphy revisited: a simple technique for complex problems. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2005;115(1):296-301; discussion 302-3. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://europepmc.org/article/med/15622267

- Becker, H., Shaw, K. E., and Kara, M. Correction of synmastia using an adjustable implant. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 115: 2124, 200Chasan, P. E. Breast capsulorrhaphy revisited: A simple technique for complex problems. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 115: 296; discussion 302, 2005.

- Baxter RA. Intracapsular allogenic dermal grafts for breast implant-related problems. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(6):1692-1698. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000086365.25453.C3

- Bahram Ghaderi, MD, Jeremy M. Hoenig, Diane Dado, MD, Juan Angelats, MD, Darl Vandevender, MD, Incidence of Intercostobrachial Nerve Injury After Transaxillary Breast Augmentation, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 22, Issue 1, January 2002, Pages 26–32, https://doi.org/10.1067/maj.2002.121957

- Bompy L, Gerenton B, Cristofari S, et al. Impact on Breastfeeding According to Implant Features in Breast Augmentation: A Multicentric Retrospective Study. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;82(1):11-14. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000001651

- The impact of cosmetic breast implants on breastfeeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis.International Breastfeeding Journal volume 9, Article number: 17 (2014)

- Spear, Scott L. M.D.; Howard, Michael A. M.D.; Boehmler, James H. M.D.; Ducic, Ivica M.D.; Low, Merv M.D.; Abbruzzesse, Mark R. M.D.. The Infected or Exposed Breast Implant: Management and Treatment Strategies. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: May 2004 – Volume 113 – Issue 6 – p 1634-1644 doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000117194.21748.02

- Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL) In Women with Breast Implants: Preliminary FDA Findings and Analyses . http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Products andMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/Breast Implants/ucm239996.htm. Accessed March 1 2016.

- Clemens, MW. Coming of age: Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma after 18 years of investigation.Clin Plast Surg.2015;42(4):605-613.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration.. 2011 update on the safety of silicone gel-filled breast implants. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/BreastImplants/UCM260090.pdf. Accessed March 2, 2012.

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: October 2012 – Volume 130 – Issue 4 – p 597e-611e.

- Alderman, Amy K. M.D., M.P.H.; Collins, E Dale M.D., M.S.; Streu, Rachel M.D.; Grotting, James C. M.D.; Sulkin, Amy L. M.P.H.; Neligan, Peter M.D.; Haeck, Phillip C. M.D.; Gutowski, Karol A. M.D.. Benchmarking Outcomes in Plastic Surgery: National Complication Rates for Abdominoplasty and Breast Augmentation ‘Outcomes Article]. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: December 2009 – Volume 124 – Issue 6 – p 2127-2133 doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181bf8378